|

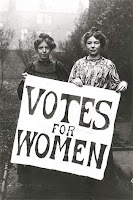

| Two Campaigners |

First I thought I’d look back to the original democracy of the ancient Athenians. Though women weren’t allowed to participate, it was the first example of a people’s parliament. In fact in Greek δημοκρατία (dēmokratía), meaning democracy literally translates as “rule of the people”. In the ancient Greek state of Athens people voted other, ordinary, people into power using shards of poetry as ballots. Those people would move on to the government offices and courts; however all citizens were allowed to speak and cast their vote in assembly, which is where the laws of the state were developed. Of course a citizen did have to fit certain regulations (they had to be Athens-born men above the age of 20 and slaves were not allowed) but this system was radically democratic, with everyone getting a say on which laws were passed.

Now we like to believe that our modern ideas have led to even greater advances in the running of first-world countries (which are nearly all democracies). The idea of everyone voting for their chosen party may be considered a lot simpler than the large gatherings and pottery slate voting system of the ancient Greeks. But in making something modern have we lost what we had in the first place? A lot of modern politics relies on parties trying to please the masses. The Conservatives have to be seen to help the lower classes so as not to appear too elitist; and the Labour Party can’t be too bound to those of lower wages as this would not appeal to those of higher wages. With every party trying their best to be the amazing cover-all solution to everything surely what we’re left with is a lot of political parties so focused on solving the problems of everyone that they will never really make anyone happy.

Aristotle is believed to have said that true democracy is everyone coming together by the ringing of a single bell in the case of an emergency. Our democracy seems to consist of everyone in power texting each other by the sounding of a single tweet. Yet in a way there are many ways in which our democracy remains faithful to the old-school ways of Athens. We vote - much like the Greeks did on pottery shards - for our MPs who then go on to speak on our behalf in Parliament. This is, in a way, extremely similar to how it happened in ancient Greece, especially considering how much other aspects, such as technology, have changed since. The only aspect which has been radically changed is that we no longer have assemblies of all citizens to decide on our laws. In addition to this, our government is no longer the top in terms of power: we now have to answer to other laws laid down by the European Union. These laws, though we abide by them, are not chosen by us; we don’t pick the leaders, movers and shakers in the EU and yet we must still go by the laws they set down. Is this a democracy? Back home in elections we vote for who we think could best match our interests, but does this mean we truly all get a fair say?

|

| Election Ballot Box |

All our diverse communities cannot be summoned by a single bell, not in Britain, let alone the wider EU. So would it be a move closer to radical democracy, or a trivialisation of serious issues, if we could cast our votes, not with a pottery shard, but with a click of a mouse?

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Hi there!

We'd love it if you'd share your thoughts and ideas. Don't forget to check back after commenting because we try to reply to all of your comments.

Just remember to be nice, please!

:)